The web is ever-changing technology landscape. Server-side developers

have a bewildering choice of long-standing heavy-weights such as Java,

C, and Perl to newer, web-focused languages such as Ruby, Clojure and

Go. It rarely matters what you choose, presuming your application works.

But how do those new to web development make an informed choice?

I hope not to start a holy war, but I’m pitting two development disciplines against each other:

- PHP

PHP was created by Rasmus Lerdorf in 1994. It is processed by an

interpreter normally installed as a module in a web server such as

Apache or Nginx.

PHP code can be intermingled with HTML. That’s not necessarily

best-practice, but those new to the language can produce useful code

very quickly. It contributed to the language’s popularity, and PHP is

now used on more than 80% of the world’s web servers. It has been helped in no small part by WordPress — a PHP Content Management System which powers a quarter of all sites.

- Node.js

Node.js was created by Ryan Dahl in 2009. It uses Google’s V8 JavaScript engine, which also powers client-side code in the Chrome web browser.

Unusually, the platform has built-in libraries to handle web requests

and responses — you don’t need a separate web server or other

dependencies.

Node.js is relatively new but has been rapidly gaining traction. It’s

used by companies including Microsoft, Yahoo, LinkedIn and PayPal.

Where’s C#, Java, Ruby, Python, Perl, Erlang, C++, Go, Dart, Scala, Haskell, etc?

An article which compared every option would be long. Would you read

it? Do you expect a single developer to know them all? I’ve restricted

this smackdown to PHP and Node.js because:

- It’s a good comparison. They’re both open source, primarily aimed at web development and applicable to similar projects.

- PHP is a long-established language but Node.js is a young upstart

receiving increased attention. Should PHP developers believe the Node.js

hype? Should they consider switching?

- I know and love the languages. I’ve been developing with PHP and

JavaScript since the late 1990s, with a few years of Node.js experience.

I’ve dabbled in other technologies, but couldn’t do them justice in

this review.

Besides, it wouldn’t matter how many languages I compared. Someone,

somewhere, would complain that I hadn’t included their favorite!

About Smackdowns

Developers spend many years honing their craft. Some have languages

thrust upon them, but those who reach Ninja level usually make their own

choice based on a host of factors. It’s subjective; you’ll promote and

defend your technology decision.

That said, Smackdowns are not

“use whatever suits you, buddy”

reviews. I will make recommendations based on my own experience,

requirements and biases. You’ll agree with some points and disagree with

others; that’s great — your comments will help others make an informed

choice.

Evaluation Methodology

PHP and Node.js are compared in the following ten rounds. Each bout

considers a general development challenge which could be applied to any

web technology. We won’t go too deep; few people will care about the

relative merits of random number generators or array sorting algorithms.

The overall winner will be the technology which wins the most rounds. Ready? Let the battle commence …

Round 1: Getting Started

How quickly can you build a “Hello World” web page? In PHP:

<?php

echo 'Hello World!';

?>

The code can be placed in any file which is interpreted by the PHP engine — typically, one with a

.php extension. Enter the URL which maps to that file in your browser and you’re done.

Admittedly, this isn’t the whole story. The code will only run via a

web server with PHP installed. (PHP has a built-in server, although it’s

best to use something more robust). Most OSs provide server software

such as IIS on Windows or Apache on Mac and Linux, although they need to

be enabled and configured. It’s often simpler to use a pre-built set-up

such as

XAMPP or a virtual OS image (such as Vagrant). Even easier: upload your file to almost any web host.

By comparison, installing Node.js is a breeze. You can either

download the installer or

use a package manager. So let’s create our web page in

hello.js:

var http = require('http');

http.createServer(function (req, res) {

res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'});

res.end('Hello World!');

}).listen(3000, '127.0.0.1');

You need to start the app from the terminal with

node hello.js

before you can visit http://127.0.0.1:3000/ in your browser. We’ve

created a small web server in five lines of code and, amazing though

that is, even those with strong client-side JavaScript experience would

struggle to understand it.

PHP is conceptually simpler and wins this round.

Those who know a few PHP statements can write something useful. It has

more software dependencies, but PHP concepts are less daunting to new

developers.

There’s a greater intellectual leap between knowing some JavaScript

and coding Node.js apps. The development approach is different from most

server-side technologies, and you need to understand fairly complex

concepts such as closures and callback functions.

Round 2: Help and Support

You won’t get far without some development assistance from the official documentation and resources such as courses, forums and

StackOverflow.

PHP wins this round easily; it has a great

manual and twenty years’ worth of Q&As. Whatever you’re doing, someone will have encountered a similar issue before.

Node.js has good documentation

but is younger and there is less help available. JavaScript has been

around as long as PHP, but the majority of assistance relates to

in-browser development. That rarely helps.

Round 3: Language Syntax

Are statements and structures logical and easy to use?

Unlike some languages and frameworks, PHP doesn’t force you to work

in a specific way and grows with you. You can start with a few

multi-line programs, add functions, progress to simple PHP4-like objects

and eventually code beautiful object-oriented MVC PHP5+ applications.

Your code may be chaotic to start with, but it’ll work and evolve with

your understanding.

PHP syntax can change between versions, but backward compatibility is generally good. Unfortunately, this has led to a problem:

PHP is a mess. For example, how do you count the number of characters in a string? Is it

count?

str_len?

strlen?

mb_strlen?

There are hundreds of functions and they can be inconsistently named.

Try writing a few lines of code without consulting the manual.

JavaScript is comparatively concise, with a few dozen core

statements. That said, the syntax attracts venom from developers because

its prototypal object model seems familiar but isn’t. You’ll also find

complaints about mathematical errors (

0.1 + 0.2 != 0.3) and type conversion confusion (

'4' + 2 == '42' and

'4' - 2 == 2) — but these situations rarely cause problems, and all languages have quirks.

PHP has benefits, but I’m awarding round three to

Node.js. The reasons include:

- JavaScript remains the world’s most misunderstood language — but, once the concepts click, it makes other languages seem cumbersome.

- JavaScript code is terse compared to PHP. For example, you’ll no longer need to translate to/from JSON and — thankfully — UTF-8.

- Full-stack developers can use JavaScript on the client and server. Your brain doesn’t need to switch modes.

- Understanding JavaScript makes you want to use it more. I couldn’t say the same for PHP.

Round 4: Development Tools

Both technologies have a good range of editors, IDEs, debuggers,

validators and other tools. I considered calling a draw but there’s one

tool which gives

Node.js an edge:

npm — the Node Package Manager. npm allows you to install and manage dependencies, set configuration variables, define scripts and more.

PHP’s

Composer project was

influenced by npm and is better in some respects. However, it’s not

provided with PHP by default, has a smaller active repository and has

made less of an impact within the community.

npm is partially responsible for the growth of build tools such as

Grunt and Gulp which have revolutionized development. PHP developers

will probably want/need to install Node.js at some point. The reverse

isn’t true.

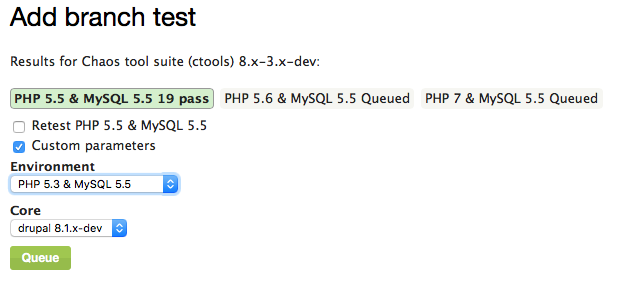

Round 5: Environments

Where can the technologies be used and deployed? Which platforms and

ecosystems are supported? Web developers often need to create

applications which aren’t strictly for the web, e.g. build tools,

migration tools, database conversion scripts, etc.

There are ways to use PHP for desktop and command-line app development.

You won’t use them. At heart, PHP is a server-side development technology. It’s good at that job but is rarely stretched beyond those boundaries.

A few years ago, JavaScript would have been considered more

restrictive. There were a few fringe technologies but its main place was

in the browser.

Node.js has changed that perception

and there has been an explosion of JavaScript projects. You can use

JavaScript everywhere — in the browser, on the server, terminal, desktop

and even embedded systems. Node.js has made JavaScript ubiquitous.

Round 6: Integration

Development technologies are restricted unless they can integrate with databases and drivers.

PHP

is strong in this area. It’s been around for many years and its

extensions system allow direct communication with a host of popular and

obscure APIs.

Node.js is catching up fast, but you may struggle to find mature integration components for older, less-popular technologies.

Round 7: Hosting and Deployment

How easy is deploying your shiny new app to a live web server? It’s another clear win for

PHP.

Contact a random selection of web hosting companies and you’ll discover

the majority offer PHP support. You’ll probably get MySQL thrown in for

a bargain price. PHP is considerably easier to sandbox and more risky

extensions can be disabled.

Node.js is a different beast and server-side apps run permanently.

You’ll need a real/virtual/cloud or specialist server environment,

ideally with root SSH access. That’s a step too far for some hosts,

especially on shared hosting where you could bring down the whole

system.

Node.js hosting will become simpler, but I doubt it’ll ever match the ease of FTP’ing a few PHP files.

Round 8: Performance

PHP is no slouch and there are projects and options which make it

faster. Even the most demanding PHP developer rarely worries about speed

but

Node.js performance is generally better. Of

course, performance is largely a consequence of the experience and care

taken by the development team but Node.js has several advantages…

Fewer Dependencies

All requests to a PHP application must be routed via a web server

which starts the PHP interpreter which runs the code. Node.js doesn’t

need so many dependencies and, while you’ll almost certainly use a

server framework such as

Express, it’s lightweight and forms part of your application.

A Smaller, Faster Interpreter

Node.js is smaller and nimbler than the PHP interpreter. It’s less

encumbered by legacy language support and Google has made a huge

investment in V8 performance.

Applications are Permanently On

PHP follows the typical client-server model. Every page request

initiates your application; you load configuration parameters, connect

to a database, fetch information and render HTML. A Node.js app runs

permanently and it need only initialize once. For example, you could

create a single database connection object which is reused by everyone

during every request. Admittedly, there are ways to implement this type

of behavior in PHP using systems such as

Memcached but it’s not a standard feature of the language.

An Event-driven, Non-Blocking I/O

PHP and most other server-side languages use an obvious blocking

execution model. When you issue a command such as fetching information

from a database, that command will complete execution before progressing

to the next statement. Node.js doesn’t (normally) wait. Instead, you

provide a callback function which is executed once the action is

complete, e.g.

DB.collection('test').find({}).toArray(process);

console.log('finished');

function process(err, recs) {

if (!err) {

console.log(recs.length + ' records returned');

}

}

In this example, the console will output ‘finished’ before ‘N records returned’ because the

process

function is called when all the data has been retrieved. In other

words, the interpreter is freed to do other work while other processes

are busy.

Note that situations are complex and there are caveats:

- Node.js/JavaScript runs on a single thread while most web servers are multi-threaded and handle requests concurrently.

- Long-running JavaScript processes for one user prevent code running for all other users unless you split tasks or use Web Workers.

- Benchmarking is subjective and flawed; you’ll find examples where

Node.js beats PHP and counter examples where PHP beats Node.js.

Developers are adept at proving whatever they believe!

- Writing asynchronous event-driven code is complex and incurs its own challenges.

I can only go from experience: my Node.js applications are noticeably

faster than PHP equivalents. Yours may not be but you’ll never know

until you try.

Round 9: Programmer Passion

This may be stretching the

“general web development challenge” objective but it’s important. It doesn’t matter whether a technology is good or bad if you dread writing code every day.

It’s a little difficult to make comparisons but relatively few PHP

developers are passionate about the language. When was the last time you

read a PHP article or saw a presentation which captivated the audience?

Perhaps everything has been said? Perhaps there’s less exposure?

Perhaps I’m not looking in the right places? There are some nice

features arriving in PHP7 but the technology has been treading water for

a few years. That said, few PHP developers berate the language.

JavaScript splits the community. There are those who love it and

those who hate it; few developers sit on the fence. However, response to

Node.js has been largely positive and the technology is riding the

crest of a wave. This is partly because it’s new and the praise may not

last but, for now,

Node.js wins this round.

Round 10: The Future

It doesn’t particularly matter which server-side language you use; it

will continue to work even if the project is abandoned (yay

ColdFusion!) Usage has possibly plateaued but many continue to use PHP.

It’s a safe bet and support looks assured for another twenty years.

The ascent of Node.js has been rapid. It offers a modern development

approach, uses the same syntax as client-side development and supports

revolutionary HTML5 features such as web sockets and server-sent events.

There has been some confusion regarding forks of the language but usage

continues to grow at an exponential rate.

Node.js will inevitably eat into PHP’s market share but I doubt it

will overtake. Both technologies have a bright future. I declare this

round a draw.

The Overall Winner

The final score: five rounds to

Node.js, four to

PHP and one draw. The result was closer than I expected and could have gone either way.

Node.js has a steep learning curve and isn’t ideal for novice developers but it wins this smackdown.

Just.

If you’re a competent JavaScript programmer who loves the language,

Node.js doesn’t disappoint. It feels fresher and offers a liberating web

development experience —

you won’t miss PHP.

But don’t discount it. PHP is alive and there’s little reason to jump

on the Node.js bandwagon because it looks faster, newer or trendier.

PHP is easier to learn yet supports proficient professional programming

techniques. Assistance is everywhere and deployment is simple. Even

die-hard Node.js developers should consider PHP for simpler websites and

apps.

My advice:

assess the options and and pick a language based on your requirements. That’s far more practical than relying on

‘vs’ articles like this!